Johannes Cabal, a necromancer of some little infamy, has this much in common with Emily Dickinson; because he could not stop for Death, she kindly stopped for him. Well, perhaps not that kindly.

This novelette was acquired and edited for Tor.com by editor Peter Joseph.

Johannes Cabal didn’t enjoy his little trips into town.

The town had a name, but he didn’t tend to use it, in much the same way that he didn’t tend to refer to the local village by any other name but “the village” and the nearest city as “the city” on those rare occasions when he had cause to mention them at all.

His strange house—tall and soot stained as if torn from the middle of a terrace and placed, brick-perfect, in the valley where nobody else cared to live (once, at any rate, he had turned up) and where no chapel bells could ever be heard no matter what the prevailing wind—his strange house provided him with privacy.

It could not, however, provide him with food. For this he required the shops of the village. There had been that early attempt to poison him but, after the trouble the village had experienced filling the vacancy for grocer, no further trouble had come from that direction. Nor could it provide him with certain supplies more esoteric than Assam tea and crumpets. If he required, for example, a particularly tortuous retort replacing after yet another small disturbance in his laboratory, then there were certain glassblowers in the city who could create it without asking more questions than were absolutely necessary. The city was a faceless place, uncaring and uninterested in the foibles—often unspeakably foul foibles—of its visitors and denizens, a great shuddering ennui that city dwellers call being “cosmopolitan” and believe a virtue. Such are the delusions and madness of crowds.

Cabal enjoyed the anonymity of the city, but was always mindful to keep his visits short. With enough provocation, even the most urbane sophisticate seemed able to lay hands upon a pitchfork and burning torch at very short notice.

This left the town, useful for the intermediate requirements. It is in the nature of towns, however, to throw up the occasional surprise, small hints to their greater metropolitan ambitions. The local town, for example, contained a hatmaker called Jones. While this fact is not so remarkable in itself, this particular hatter maintained a sideline of such startling occultness that the very method by which Cabal discovered it would be a lengthy account in itself. It would not, however, be an engaging one so we must be satisfied that Jones had a sideline, Cabal had an interest, and they both had a financial understanding.

Twice a year Cabal would make his way to town and enter the hattery through the grimy alley backing it. They would meet in the storeroom and, with no pleasantries, Cabal would gives Jones a sum of money, Jones would give Cabal several small paper packages, Cabal would arrange the date of his next visit as he carefully stored the packages in his Gladstone bag, and then he would leave the way he had come, again without pleasantries.

Cabal didn’t enjoy these visits for a variety of reasons. He didn’t enjoy the trip; while the majority was aboard a suburban train, the stretch between his house and the village was four miles along a country road, muddy half the year and dust for the rest. He would have taken his bicycle, but for the fact that the last time he had left it at the station, he had returned to find its spokes kicked out and its tyres slashed. It appeared that the respect the villagers held for him—“respect” here used as a synonym for “fear”—did not extend to his bicycle. He had not yet got around to identifying and formulating a punishment for the malefactor, but when he did he would be sure to make it more than sufficient to prevent any further interference with his property.

Nor did he like the town itself very much. Caught in the sticky patch between a collapse in local light industry and whatever was going to come along to replace it, the place was coasting along on its municipal laurels, if one can imagine such a thing. The streets were swept rarely and with little conviction, the shop windows collected dead flies, and past dignitaries, struck in dramatic poses to exhort a missing populace to greater things, looked down upon an empty town square. But these long dead orators gathered no crowds now, only pigeon guano. Jones insisted that Cabal approach the shop by the alley backing it, an exasperating insistence given the infrequency of passersby on the high street to the front.

Paranoia was the third of the reasons Cabal disliked his visits to Jones’s shop. Not his own; it is not paranoia when one believes people are out to “get” one and one happens to be a necromancer—it is a certainty. No, Cabal harboured suspicions of Jones’s state of mind. On his last visit, Jones had spent almost the entire time at the window, peering through the dusty blinds into the street, impatiently gesturing Cabal to leave the money, impatiently gesturing Cabal to take the packages.

Cabal didn’t take well to being impatiently gestured at and prolonged his stay.

“Why so eager to see me go, Herr Jones?” Cabal had asked, stowing the paper packages into his bag with exaggerated care.

Jones had looked at him, slightly shocked, and Cabal had realised that he wasn’t aware of how obvious his behaviour was.

“The . . . things I get for you, Mr Cabal, the materials. I . . . you appreciate their rarity?”

“This wouldn’t be an opening to a conversation about rising prices, would it?”

“No! No, but . . . there is great danger. The things I have to do! Terrible crimes against the Fay! The Seelie and the Unseelie, they have long memories.”

Cabal had joined him at the window and they had looked out together into the withered town. “Not a good location for faerie rings, is it? I daresay the civic fathers overlooked the inclusion of sylvan glades and shady bowers in their municipal planning, too.” He had gone back to packing his bag, this time working quickly, the sooner to be quit of that place. “You worry too much, Jones. I’ve had run-ins with them in the past and they’re all twinkle-dust and no trousers. The Fay, that is—not the civic fathers. The Fay’s powers are on the wane—places like this are crushing the life from them. You’d be wiser to focus your energies upon keeping your customers happy. In both of your lines.”

In hindsight, perhaps Jones had taken that as a threat, and Cabal now regretted his choice of words. He suspected his next visit would be all the less pleasant because of it.

And now, that time had arrived. He stepped out onto his doorstep, checked that the door was locked, picked up his Gladstone bag, and set off.

As he walked down his garden path, he was very aware of countless small eyes watching him from the concealment of the flower beds. The things in the garden were, by strict dictionary definition, fairies themselves, but would have as soon doused themselves in holy water as worn a bluebell for a hat or any of the other mimsy nonsense usually associated with their kith. He didn’t see them often, but the last one he’d caught a glimpse of had been wearing a rat skull as a cap over its sharp little face.

If they had been useful as a source of the specialist materials that Jones supplied, Cabal would have been quite happy—possibly even delighted—to cull the whole snickering mob of them. They were, however, of the basest kind, and any strange essences he might be able to wring from them would be polluted and likely to cause problems with Cabal’s current line of research. All things considered, Cabal was quite happy to let Jones do all the hard work of traipsing around faerie mounds with butterfly net and mangle. Besides, the things in his garden had their uses. Not many salesmen ever reached his door, and the ones who did never made it back to the gate.

Today there were none of the usual tiny good-natured jeers from the things of the garden about his parentage, personal habits, and appearance; perhaps they sensed his business. He closed the garden gate behind him and set off towards the village station.

Walking helped him to think and, today, he was thinking what an unpleasant day it was to be walking. The air hung humid and still and he was disagreeably aware that he was sweating. Cabal regarded sweating as one of Nature’s more subtle revenges upon humanity and its pretensions to Prime Species. It is hard to regard oneself as civilised when one oozes in warm weather. Cabal was doubly cursed by his wardrobe: a black suit and hat—a snap-brimmed thing of American lineage he had bought in a moment of madness at Jones’s shop—black shoes, socks, and thin cravat. It soaked up the sun and Cabal perspired, his habitually bad mood sinking from the dreadful towards the foul.

If the coach hadn’t been such a surprise, he would have been glad for the shade it abruptly cast upon him. As it was, he whirled as the daylight was blotted out and stepped back, causing the sun to fall once again upon his face. Through his blue-tinted glass spectacles, the coach body was black and without detail, a sudden phenomena as unexpected as a rain of fish. He looked up and down the road. How had he not heard its approach? Why was there no dust in the air to mark its passage? He moved off to one side, the better to examine it.

The coach was a well-appointed landau in the Sefton style, sitting motionless on its helically sprung suspension. In the traces were two huge, black stallions. Belgian blacks, unless Cabal was mistaken, a breed often used for drawing hearses.

Black as the horses, black as the livery, was the look the coachman was giving him. There was nothing individually disreputable or malevolent in the man’s clothing—the road coat and cape, the thick scarf over his lower face, the diminished top hat of the Müller sort, all as black as a banker’s soul. But the way they hung on him, gathered on him like crows on a gibbet, was almost unnerving. Cabal felt ill-matched to the weather in a suit, but this man was wearing a coat and scarf. They regarded each other for a long moment, Cabal’s eyes guarded behind blue glass, the coachman’s invisible behind heavy goggles. There was no inkling of intent or attitude in his posture until, finally, he turned away to gaze moodily or philosophically—it was impossible to tell—at the horses’ arses arrayed before him. Cabal felt he should have been insulted, yet somehow, as he looked at the coachman’s hunched shoulders, it seemed like a waste of energy, like taking offence at a weather cock for swinging away.

Actually, now that he looked more closely at those hunched shoulders, he had a momentary impression of movement beneath the cloth, from the shoulders down, under the obscuring mass of coat. As if, fancifully enough, the man had wings.

Not fanciful by nature, Cabal immediately turned his attention to the coach itself. As he did so, the door opened. He noted that it had done so without the door handle moving, which seemed ill-mannered. Inside there was little but gloom, shadows of the bright day. Feeling his usual state of irritation with the world and most of the things in it settle upon him like a cloud of lice, Cabal took off his sunglasses, the better to see within.

The woman was beautiful, of that there was no doubt. She was white and red and black: her skin; her hair and lips; her dress. And her eyes were dark too, and as soulless as a waxwork. To look into them was to look into space. Despite the warmth of the day and the sweat that dampened his shirt, he felt a strange chilling frisson that, while not entirely unpleasant, was still some way short of pleasant. They looked at each other for a long moment, she in her widow’s weeds, he in his disgruntlement.

“If you’re looking for the cemetery,” he said finally, “you’re on entirely the wrong road.” He made a mental note to check the recent burials for likely experimental material.

“Get in,” she said, ignoring the comment. “You and I, we are travelling the same road, at least for a little way.”

As it happened, this was self-evidently true. But Cabal did not care to jump into the carriages of strangers. That way lay a sack over the head, a cosh to the skull, and, if he was lucky, a shallow grave in scrubland. “I’ll walk,” he said, turned, took a step, and found himself sitting down opposite the woman. The door swung shut and the carriage rattled on. Cabal looked about in consternation. At no point had he decided to place his foot upon the step, hoist himself into the carriage, and take the seat. No matter. He would just leave. It would not be the first time he’d jumped from a moving carriage.

He reached for the handle and discovered that there wasn’t one. He paused for a furious moment. He could search for one, but this was all looking very much like a fait accompli. Scrabbling around at the door would probably just make him appear an idiot, even more than an idiot who enters a carriage without meaning to. Instead, he sat back and looked at the woman steadily. There was an element of glaring in the look, but he couldn’t help that.

“Thank you for your offer. If you’d be so kind as to drop me off at the railway station, I should be most obliged.”

They travelled in silence for all of two minutes before the women spoke, her voice quiet and musical. “This is a lonely road you travel, Mr Cabal.”

Ah, thought Cabal. So begins the double talk. I shall have none of it.

“You clearly know who I am. I don’t believe that you simply happened to be passing, and I do not believe that I could have made such a mess of the simple act of avoiding joining you in here without assistance. I am a busy man”—he saw no evidence of a wedding ring beneath the black lace of her gloves and ventured a—“fräulein. I would ask of you that you dispense with your attempts at tact, disingenuity, and abstruse conversation. If you have something to say, say it.”

To his great and rising irritation, she was not at all put out but only smiled sweetly, as at a small child who has made an imperfect attempt upon a three-syllable word.

They travelled in silence for a further two minutes.

Finally the women spoke again, her voice quiet and musical. “This is a lonely road you travel, Mr Cabal.”

Cabal was assailed by a strong sense of déjà vu, not simply from the repetition of the words but also from the small hillock, topped by an old elm, that he could see out the window. He was sure he had been looking at that exact tree when she had spoken the last time. He began to understand the rules of this game and, having no desire to spend the rest of the day seeing the same elm on the same hillock, he decided that he would play, albeit not in the most sporting frame of mind.

“I prefer to travel alone.”

Infuriatingly, her smile deepened. “But was that always the way? In your dreams, is that the way still? Or do you wish to go back a ways? To twist a thread whole that cruel Atropos . . .”

Cabal’s lips grew thin, his colour pallid. “You, madam, are on dangerous ground . . .” he said, so quietly that it was lost in the hoofbeats and creaking of wood.

Yet, she seemed to hear him, and yet, she didn’t care.

“. . . that cruel Atropos cut so short.” Her eyes shined as she spoke, harsh icy crystals of something like cruelty in every syllable.

“Shut up!” Cabal was suddenly furious, his tightly reined anger breaking loose. “Shut your verdammt mouth! You think you can just kidnap me in this fashion and I don’t know who you are?” He fumbled in his pocket and took out a small piece of pitted metal that he placed with venomous swiftness on her pale flesh between cuff and glove. She watched him with amused eyes as he, face white with fury, breath shuddering, pressed the metal harder onto her skin.

“What do you expect to happen?” she asked, politely interested.

Cabal’s fury left him as quickly as it had materialised. He looked at the piece of metal, her wrist, the metal again, and finally dropped it into his pocket. He swept back his short blond hair as he regained his composure. “I’m sorry, fräulein. Your questions were too impertinent to tolerate but, still . . .” His loss of control had frightened him far more than it had her.

“What was that?” she murmured calmly, pointing vaguely at his pocket.

“Meteoric cold iron. I . . . forgive me . . . I assumed that you were of the Fay. It would have burned you if you were. I was obviously mistaken.” He coughed, embarrassed. “My current line of experimentation, I almost expect reprisals.”

The elm tree on its hillock went by again.

“You are right in one respect, Mr Cabal. Time is short. Perhaps shorter than you realise. We have touched, briefly if not briefly enough, upon your past, and you speak of your present endeavours. But I . . .” She reached to the side of the carriage and drew down a folding tabletop until it lay across her lap. Then, nonchalantly and without affectation, she produced a deck of cards from thin air and spread them facedown. Taking the last card, she slid it beneath the end of the spread and flipped it over. The cards obediently flowed onto their backs in a wave, showing their faces. Cabal winced slightly. Tarot cards. “I deal with people’s futures. Or”—she held up the card she was holding so Cabal could see its face—“the lack of same.”

It was the thirteenth card. Death. Unusually, Death was not represented by a skeleton with a scythe. Instead, the card showed a carriage upon a lonely road. From its window, a woman in black and red and white looked out.

“Ah,” said Cabal.

She did him the courtesy of looking down as she gathered up the cards, affecting to ignore his confusion and dismay. “You and I are not enemies, Johannes.” She looked up and smiled brightly at him. “You don’t mind if I call you ‘Johannes,’ do you?” Cabal, finding diplomacy and self-preservation might well be the same thing at that moment, did not. “We are not enemies, no matter how much you might believe that. Your enemy is time.” She gestured out of the window, where the elm was just going by again.

“A nicety.” Cabal was recovering his composure.

“Not at all. A fundamental point.” She held out the cards to him. Lips pursed, he cut the deck. She smiled pleasantly and started to lay them out. “Nobody knows when your time is up.”

“You do.”

“I don’t.” She finished laying out the cards into a fortune-teller’s spread. She saw his raised eyebrow. “No. I don’t. But when the time comes, it’s clear enough. There are always indicators. Of past” —she tapped the cards as she spoke—“present, and, my abiding interest, the future.” She flipped the card over.

Cabal craned his neck to look. “Card X. The Wheel. That’s good, I believe.”

“For most people who don’t do what you do, it is. Do you believe in karma?”

“No.”

“That’s a shame, because this card does.” She started to gather up the cards again. “I think we need to exercise some alternative technique.”

He stopped her. “Please. Humour my curiosity.” He turned the card marking his past.

“The Lovers, Johannes. My, my, my,” she remarked mildly.

He sniffed and turned the card marking his present. “Card I. The Conjuror. Ha!”

She took the card and looked at it for a moment before turning its face towards him. “Are you sure?” Cabal looked again. Card 0. The Fool.

She slid the card back into the deck and shuffled it. “I always get them mixed up myself.”

Cabal watched her for a moment before asking, “Why this concern? There are many within my profession, such as it is. Well, a few, at any rate. Do they all receive visitations such as this?”

“No, Johannes. They do not. You are a special case.”

“Special?” That sounded dangerous. “In what way?”

But the woman wasn’t listening. Before returning the card marking Cabal’s past to the deck, she had flipped it in her hand and was looking intently at it. “Just special,” she said distractedly. She returned it to the deck and gave Cabal a look he couldn’t decipher at all. “Give me your hand,” she said tonelessly, unsmiling.

With mild trepidation, Cabal held out his right hand. She took off her gloves before taking his hand in hers. Her skin was smooth and cool; Cabal found himself thinking of the statue of a medieval lady, buried by her husband in a church crypt that he had once visited, lady-size in marble. If the woman noticed the faint shudder that ran through him, she didn’t show it.

“A long middle finger. Strong thumb.”

Cabal was interested despite himself. “Meaning what?”

“Meaning that you’re probably very good at flicking things.” Her smile returned, more mischievous than before. “Oh, and some other things, but they’re not relevant.” She turned his hand palm upwards and the smile vanished. She looked at him very seriously. “All of which brings us to my interest in you, Johannes Cabal.”

“Yes, your interest in me,” replied Cabal evenly, while wondering how far he would get if he flung himself out of the carriage window. He had a depressing sense that the glass wouldn’t shatter.

She turned his hand so he could see the palm and indicated an area from the web between the thumb and forefinger down in an arc to the middle of the wrist. “Do you know what’s missing from here?”

“You know, the Gypsy Petulengro neglected to mention any . . .”

She stopped him. “I’ve heard about your brand of wit. Keep it to yourself.” She indicated his palm again. “You’re walking around without a life line, Johannes. That simply isn’t done.”

“Life line?” Baffled, he took his hand back and studied his palm. Now that she mentioned it, it didn’t look nearly as cluttered as perhaps it should. He had memories of a line running just as she had shown him, running around the base of the thenar eminence. Now, there was nothing but the expected fine geography of minute peaks and troughs. He looked up at her suspiciously. “A freakish happenstance, nothing more. Why your interest?”

“Not just a freakish happenstance, Johannes. It’s against the rules.”

“Whose rules?”

“Mine. And I tend to have the last word in disputes. Now, how did you happen to lose your life line? Think carefully now.” The smile was back. Cabal had a sense of a cat trifling with a mouse, or vole, or some other small rodent, and he didn’t care for it at all, no matter who she was.

“I dislike being toyed with,” he said sharply.

“I know you do,” she replied, as if speaking to a four-year-old. She dropped the demeanour like a mask, but kept a colder incarnation of the smile. “I know a great deal about you. I know you think you can cheat me.”

“I have cheated you. I died. I got over it.”

“You managed it once. Don’t get all cocky and think you can manage it again. You haven’t cheated anything at all. Only postponed the inevitable. Which brings us back”—she took his hand again and levered it over so she could see his palm. She did it with such unexpected strength that Cabal gasped involuntarily—“to this.” She smiled, without a shred of humour. “What shall we do to make things right again, Johannes?”

She wasn’t releasing her grip and Cabal found the pain was escalating. It was hard to accept that the young—if only in appearance—lady sitting opposite him was applying the sort of pressure more usually associated with bull gorillas with something to prove. He was past pain now, tending into the foothills of agony.

“Are you open to suggestions?” he managed without sobbing.

“No. On this occasion, I think I already have the solution.”

She placed the tip of her free thumb gently on the skin between the bases of his thumb and forefinger. Then, with a sudden vicious push, she drove her nail into the flesh.

Cabal’s agony rocketed from the merely very unpleasant to the incandescent in a heartbeat. He couldn’t draw breath to scream, his feet scrabbled helplessly on the carriage floor, his free hand grabbed the edge of the seat, and his fingers dug into the upholstery. He could feel the bones crushing together within her grip, could feel them breaking and breaking again. He wanted to collapse, but she held his hand as effortlessly immobile as if she really were that marble statue, held his hand free from the slightest quiver as she drew her nail across his palm, skirting the thenar eminence, slowly and deliberately cutting his hand open. The flesh peeled back beneath her nail, sharper than any scalpel, peeled back the subcutaneous layer, the flesh beneath, musculature, blood vessels parting, down to the white bone in its red setting. Blood sluiced down his wrist, soaking his shirtsleeve.

Suddenly he was in the road, rolling facedown in the dust. His bag landed with a thump beside his head. As he blinked away tears of pain, as he hugged and cosseted his maimed hand to his chest, he heard her say, “Remember, Cabal. You haven’t cheated anything at all. Only postponed the inevitable. Those are the rules.”

He rolled over, spitting foul invectives in three dead languages. And found he was cursing a milestone. Of the carriage, the horses, the coachman, and the passenger, there was no sign at all.

He was past being surprised. It didn’t surprise him that the milestone showed that his lengthy ride in the carriage had carried him less than half a mile. It didn’t surprise him that, on turning, he found himself facing a small hillock topped with an old elm. It didn’t surprise him when he risked a glance at his crushed and slashed hand that . . . .

He blinked. No, he concluded, actually this was quite surprising. His hand seemed unmarked, undamaged. No mangled fingers, no bloody rivulet trailing from his grip, no red-soaked sleeve, nothing at all. Except… He angled his hand to examine the palm more closely in the sunlight. Except that now he had a life line. It looked like it had always been there; it looked as if it belonged. Apart from the slight itching tingle that travelled through the skin, there was nothing to tell it apart from any other line upon his hand.

He frowned. All this trouble for a crease in the skin? The attention of a higher power for this? He rubbed experimentally at it, but it remained.

Cabal took out his pocket watch. His capacity to accept the inexplicable that morning had been raised to such a high mark that he hardly registered more surprise than warranted a slight sniff when he discovered that a little less than two minutes had passed since he last checked it, moments before the carriage had appeared. He still had time to get to the station. But, he would still have to walk. Picking up his bag, Johannes Cabal started along the road once more.

After he had been let into the storeroom to the rear of the hatter’s shop, Cabal dropped his bag heavily on an old worktable and leaned there, both palms upon the tabletop, while he marshalled himself.

“I have experienced a very bad day thus far, Mr Jones. I hope you are not going to add to my sorrows.”

When he received no reply, he turned his head to look at the nervous hatter. Jones hardly seemed to be listening. He was at his habitual place at the window, twitching the blinds. Cabal bit back his frustration with the man’s lack of focus. It had taken a long time to cultivate Jones, to make him trust Cabal enough to use his peculiar talents to supply Cabal’s needs. As it was, Cabal was coming to the conclusion that the whole line of investigation might be fundamentally flawed and that he would be bringing it to a halt soon enough anyway. Still, it was worth the extinction of a few dozen more fluttering woodland types to be sure. When Cabal had read Peter Pan as a boy, he had found himself thinking, Yes, I do believe in fairies. But I still want you to die.

“Well, enough of the pleasantries,” said Cabal when he still had no reply. “Have you gathered my supplies, Herr Jones?”

Jones still did not reply. “What precisely are you looking at?” Cabal asked, joining him at the window. They gazed down into the dusty, uninteresting street. It looked uninteresting, but for the dustiness. Cabal felt unilluminated and strangely out of sorts. He’d felt unpleasantly detached from the full experience of reality ever since that nonsense in the carriage with . . . .

He looked down at his life line. He hadn’t even noticed that it had gone. When he had—for the lack of a better term—died that time, the state of his palm print on returning from that Dark Vale of—ironically enough—No Return had not been of much concern. Now, he couldn’t stop sneaking faux-casual glances at his palm.

“I fear death, Mr Cabal,” said Jones quietly, his eyes still upon the empty street.

The words so closely matched Cabal’s own thoughts that he was hardly aware that they had been spoken at all. “I was dead once,” said Cabal distractedly, his attention upon his hand. He didn’t see Jones’s sudden, frightened glance at him. “Years ago. An experiment. I suspended my vital signs for nine minutes and forty-four seconds. I was looking for inspiration, an understanding.” The sight of his restored life line fascinated him. “I didn’t find one. The laboratory grew dark, and then I awoke. Only my instruments assured me that I hadn’t simply fallen asleep.”

“Did . . . did you see anything?” Jones was terrified to ask, terrified not to.

“No. Nothing at all. No afterlife. Although . . . There is a Hell.”

“Hell? How do . . . ?”

“I’ve seen it. Visited. I was alive on that occasion. It wasn’t a pleasant day trip. It wasn’t a pleasant year.” He frowned. This was a conundrum. “I wonder how it was that I didn’t see anything? I would have certainly . . . Oh. Of course.” He smiled to himself, how had he forgotten that small detail. “I had no soul.”

It was a small omission. If he had continued the sentence a little further to include “but I have one now,” things might have turned out differently. Cabal realised that later when he analysed the day’s events, but—right then—it seemed an unimportant point. A tiny bit of happenstance that, for scientific reasons, he had seen fit to sell away his soul and that later, for scientific reasons, he had seen fit to recover it.

He certainly didn’t appreciate its significance at the time, when it might have done some good. The sight of Jones going quite mad with fear unduly distracted him from that conclusion.

“You!” said Jones, backing away. “It’s you!”

“Of course it’s me,” replied Cabal.

This, he was later to realise, was exactly the wrong thing to say at that juncture.

Jones spoke, but it was in such a paroxysm of dread and terror that the words fell over one another and became shrill, sobbing gibberish. Cabal watched him, utterly nonplussed. What had got into the man?

Perhaps, Cabal conjectured with a growing sense of threat, Jones’s paranoia had gone too far. Perhaps he, Cabal, had asked Jones to risk his neck once too often. Perhaps Jones had been keeping himself busy between excursions and the rare occasions when anybody actually wanted a hat by constructing an imaginary world of menace and conspiracy—a world that Cabal had accidentally tapped into with his apparently ill-omened comment.

What happened next happened quickly and Cabal was hardly aware of the chain of events even as they occurred. He simply responded to stimuli, reasoned rapidly and without reflection, and acted upon that reasoning.

Jones continued to move away from him until he reached the end of the table. His eyes flickered down and he reached for the handle of one of the table’s drawers. Cabal watched him with cautious curiosity, but no real sense of danger.

Then the pain began.

It was the living echo of the agony he had felt earlier that same day, burning across his hand as if the flesh was being laid open with a blade of frozen vitriol. He gasped with its suddenness and gripped the stricken hand with the other as he looked down at the open palm. What he saw first confused, then horrified him. His life line was shortening before his eyes, burning like a fast fuse across the skin. He could see the crease vanishing in a bead of boiling blood, leaving nothing but smooth skin behind it.

He looked up: Jones had the drawer open, looking furtively at Cabal as he searched in it.

Cabal reached for his bag, undid its strap and buckle in two fast twitches, shook it open.

Jones had found what he was looking for, closed his hand around it.

Cabal reached into the bag with his right hand, ignoring the pain. When his hand closed around the butt of his Webley, the cool wood and metal seemed to ease the burning. He let the bag fall, lifting the gun and thumb cocking its hammer at the same time.

Jones had a knife, an ugly, large thing made of some crudely refined metal and placed in a lightly coloured wooden handle. The expression of panicked hope in his face dissolved as he saw the gun. He whimpered and Cabal shot him.

The shot was placed to kill instantly and it could hardly miss at that range. Jones was dead before he even started to fall. By the time his head cracked against the floor, Cabal was already preparing his departure.

He gathered up the particular materials he had come to buy, wrapped them in a large square of butcher’s paper, and packed them into his bag, placing the revolver upon the top of it in case it was needed in a hurry again. He strapped the bag shut and made as if to leave. Instead, he paused and looked back at Jones. Poor, paranoid, very dead Jones.

At least, he assumed Jones was dead. He’d never heard of anybody surviving a Boxer .577 round delivered at close range to the interorbital space, but that wasn’t to say he should take it as a given. He stood over Jones and looked at the damage. On examination, it appeared very much like one could take death by Boxer .577 round delivered at close range to the interorbital space as a given. Cabal sighed. He disliked killing, doubly so when it represented a nuisance to him quite apart from the judicial ramifications. He was quite adept at running away from the police and bribing the few that lasted the course. The loss of Jones, however, made gathering the specialist materials Jones had been supplying quite difficult. Speaking of which.

Cabal knelt and picked up the unwieldy knife Jones had made to attack him with. The blade was of some form of barely refined metal, certainly not steel. Iron? he wondered. But why? It wouldn’t hold an edge for long, it would rust easily, and it simply didn’t make much sense for anybody to . . . .

Suddenly reaching a conclusion can bring a bolt of pleasure or a stab of dismay. This was definitely the latter. Cabal reached into his pocket and found the small piece of meteoric iron he kept with him and held it alongside the blade. While not the most thorough of metallurgical tests, there was still an undeniable similarity.

With a sinking heart, Cabal looked at his right palm. There was his life line, just as it had always been there. Of course it was.

Cabal stood, placed the metal in his pocket, put the knife into his bag to lie alongside his revolver, and left Jones’s hat shop for the last time. He had killed once today in self-defence. He strongly suspected that he would kill again before the day was out, but this time it would be in revenge.

As anticipated, the train trip passed without incident. Also as anticipated, the walk home didn’t. As he walked past a small hillock topped by an old elm, he suddenly found himself in shadow. He turned expecting to find the black landau, the black horses, the black-clad coachman sitting and waiting. Thus, Cabal was not disappointed in most of his expectations. The coachman, however, was far more proactive than at their last meeting. As Cabal turned, the coachman grabbed his wrist, tore his Gladstone bag from his hand, and tossed it to the verge of the road as if it were dripping pus. Before Cabal could protest, the coachman had opened the landau’s door, picked Cabal up by the scruff of his jacket, and thrown him in. The adjective unceremonious occurred to him as he landed face-first on the carriage’s floor. Disconcerting as his first entrance to the carriage had been, it seemed greatly preferable to the second. He heard the door slam shut.

“Are you all right down there?” she asked.

“Oh, good,” he replied as he climbed into the seat facing her. “Insult to injury. Why no legerdemain this time? Run out of pixie dust or just couldn’t be bothered? After all, you’ve won your little game, haven’t you?”

She looked at him, silent and serious, for several seconds. “Not a game, Mr Cabal. No game at all.”

“No game,” said Cabal in a low, dangerous voice. “No game? You have . . . manipulated me right from the moment I first saw you. Induced me to draw false inferences. I should have thought something was wrong. The black landau, the black horses, the silent coachman, the widow’s weeds—it was all so much more . . . banal than I would have expected.”

“Then why did you believe?”

“Because . . . because supernatural entities insist on melodrama. I’ve met Satan. Did you know that? He is such a drama . . . What is the phrase?”

“Queen?” She seemed amused.

“Yes, just so. Brimstone, devils, fiery depths, cribbage. It is all so theatrical.” He considered. “Well, perhaps not the cribbage. I think that’s more of a hobby. But the point is that when a mysterious funereal black carriage materialises out of thin air, abducts me, alters the passage of time, and its occupant lectures me on fate and life expectations, I apply Occam’s Razor and arrive at the obvious solution.”

“Which was . . . ?”

“Which was that you are Death.”

“I never said it,” she said, serious again.

“You didn’t. You just implied it with sledgehammer subtlety and I accepted it, based on the evidence. There was only one other alternative, and that I proved was not the case. At least”—he took the piece of cold iron from his pocket and held it up—“I thought I’d proved it.” He watched her. She seemed calm, but her eyes never wavered from the small bit of metal. “You are of the Fay, aren’t you? I admit, you still have me at a loss to explain the lack of reaction. The metal should have burned you.”

“You have a reputation for great deductive powers, Mr Cabal. I shan’t insult you by offering a solution.”

He hardly heard her. The threads were finally coming together. “Unless, of course, you are not of pure blood. Your mortal heritage would prevent the worst physical effects.”

She nodded. “Your reputation is well-earned.”

“I would thank you not to patronise me, fräulein. I have killed on your behalf. I am not happy about it.”

“Jones was a murderer, and you were his employer, Cabal. You should be thankful that you are not sharing his fate.”

“I should kill you.”

“You should not. You would surely die in the attempt, especially without Jones’s filthy knife.” She saw Cabal’s expression. “Oh, with Jones dead, the defences he’d placed upon his shop collapsed. It was searched as soon as you had skulked out of the door.” Cabal began to protest that he did not skulk, but she talked over him. “I would have been far more surprised if you had not taken the knife with you.”

Cabal weighed the piece of metal in his hand. It seemed altogether too feeble an ace to do him any good at this juncture. He slid it back into his pocket. “This all seems very calculated.”

“It has been planned for a long time. You should be flattered, Cabal. Both the Seelie and the Unseelie Courts cooperated in this. It takes a great deal to make them sit down together.”

“But you . . . you planned this for them. I have had dealings with the Fay before. They lack the detachment shown here. It would have all been hellhounds and ogres if left to them. The piece of theatre with the life line”—he paused to look at his palm— “very cunning. You made me aware of my own mortality and the mechanism to make me fear for it all at the same time. How did you prime Jones? His paranoia was quite evident. What did you use? A few anonymous letters? Some carefully ambiguous evidence that I was planning to betray him to the Fay? No wonder he was so fascinated about what comes after life. No wonder he startled so violently when I mentioned that, once, I had no soul. Proof positive to his terrified little mind that I am as you. I might have been able to calm him except, thanks to this verdammten line you placed on my palm starting to disappear, I was convinced that I was going to die within seconds, apparently at Jones’s hand. And while we were both . . .”

“Panicking?”

“Distracted from rational thought, we attacked each other. How could you be sure Jones would be dead at the end of it all, though.”

“You had a gun, he had a knife. It was the probability.”

“But, if I’d not been able to reach my gun in time . . . ?”

“He would have killed his only client. He would have had no reason to carry on harvesting us. Either way, we win. There were plenty who hoped that you would kill each other.”

“And you? I can’t help wondering why you have bothered to intercept me now the deed is done. The only conclusion I can reach is that you intend to kill me too. Perhaps crow a little of how clever you have been, but kill me nonetheless.”

“I’m not the crowing type,” she said, and Cabal was more sorry than he had been at any point since entering the carriage that he did not have Jones’s cold iron blade. “Nor am I a killer. I researched you very carefully before arriving at this stratagem, Cabal. I have no need to kill you, or even the desire. My father was a poet, my mother Leanan-sidhe.”

“A vampire, then.”

“A muse. I understand the human soul, even one as ill-used, as lost-and-found as yours. That is why I am going to let you go. One day you may understand why.”

“Deferred gratification. The story of my life.” He opened the door. She had promised him his life but she was, after all, a woman. The fact that she was half-Fay didn’t help her reliability.

As he made to step down, he paused. “A moment,” he said over his shoulder. She raised an eyebrow. “You say that you are half-mortal, half-Sidhe?”

“I hope you don’t intend your parting comment to be something spiteful about mongrels, Mr Cabal?”

“Not at all. It occurs to me, though, that even if cold iron does not burn you, its touch should have still been agonising. Yet, you did not flinch.”

“And what does that tell you?”

He stepped down, closed the door, and doffed his hat. “Auf Wiedersehen, fräulein. Most respectfully, I hope and trust that we don’t meet again.”

“And yet you say ‘Auf Wiedershen.’”

He ignored her evident amusement. “May I know your name? Just so I can add you to my lengthy list of people to avoid.”

“Myghin,” she replied, her humour undiminished. She pronounced it May-xuhn. “I have a title, too, but I’m not a one to stand upon ceremony. Slane lhiat, Mr Cabal. May we never meet again, for the best of reasons.”

She sat back and the coachman, acting on an unheard signal, drove on. Cabal watched the black coach travel down the dusty road until it was lost in a moment of heat haze. He was unsurprised when it failed to reappear.

It took him almost a hundred minutes to complete the walk home. He paused in his front garden and looked at the shrubs he knew sheltered small, villainous fairies. “Have you been talking to strange ladies?” he asked, neither expecting nor receiving an answer. He unlocked the door and went in.

After a cool bath, he retired to the parlour with a simple supper of cold meat, bread, and a pot of tea. As he ate, he started to transfer notes from his daybook to the permanent record book, but gave up after a few minutes. His heart really was not in it. He sighed and went to the window to watch the shadows cast into the valley by the low sun. It had been, he concluded, a strange day. Even by his standards.

Finally he walked to the shelves and took down a book he hadn’t read in years. He settled himself back at the table, took a sip of tea, and started to read.

“To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman.”

“The Death of Me” Copyright © 2013 by Jonathan L. Howard

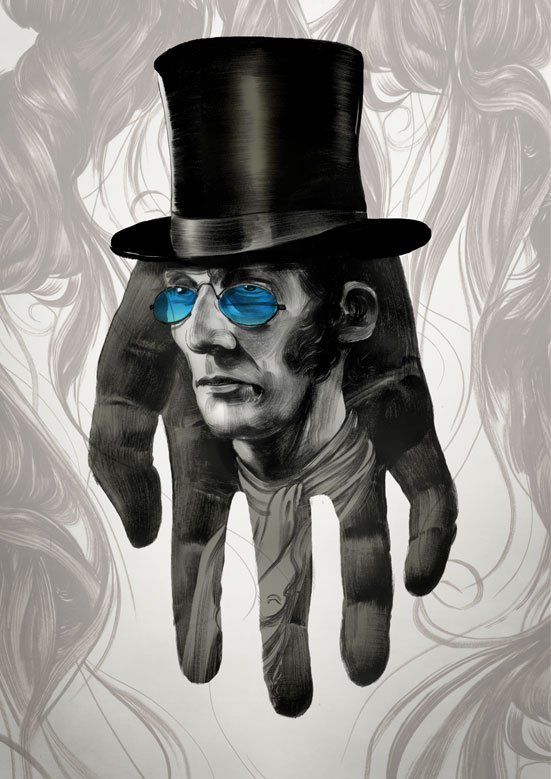

Art copyright © 2013 by Greg Ruth

Thank you so much for sharing this with us! I have been waiting for a new Cabal novel, maybe that’s in the works too?!

Very very nice….

Quite good. I shall now be looking up the books.

Boy, did I like that.

This was wonderful. Your novels have just been given priority spots on my to-read list.

Edited to add: Just read The Fear Institute! (It was the first one I could get my hands on.) Loved it, loved it. Now to read the first two novels!